Wednesday | September 25, 1985

On reaching the shores of England, embarked on the train journey on their way to the city, one of Lamming’s Emigrants remarks:

“Look partner dat’s where they make the blades, partner, all yuh shaving you say

you shave you do cause o’ that place. Look it, ol’ man, they make yuh blades there.

Ponds, ol’ man, look Ponds. They make cream there. All those women back home

depend on what happen in there. Look Ponds Cream. Look Tornado you see that.

Paint. They make paint there. Look Paint. You dint see that, partner. You see that.

They make life there. Life. What life partner. Where you see they make what.

Life partner. Read it. Hermivita gives life. You ain’t see it.

In the same direction, look, they make death there, ol’ man. Look, Dissecticide kills

once and for all. Read partner. Look what they make.

They make everything here on this side. All England like this.

Everything we get back home they make here, ol’ man.”

Yes, they make from life to death over there. This was the way of the colonial economic order. The mother country made, the commission agents at home sold. Lewis, our Nobel Prize winner suggested otherwise. In his “Industrialisation of the British West Indies” he advocated industrialisation. We should invite entrepreneurs from abroad to locate factories here, both on their own account and in joint ventures. We should provide incentives.

But we should be careful; we should choose those industries or activities which would need protection for a finite period. We should choose infant industries which would ultimately grow up.

The merchants and commission agents initially fought this. Then they realized all they needed to do was import the product at an earlier stage of processing. They put all their weight behind the programme. Lewis’ warning was not heeded. Indiscriminately industries, screwdriver industries, mushroomed. Quality fell in many cases. The infants never grew up — save the very few. The consumer was held to ransom. Industry provided jobs, added to GDP while providing technical training and technological innovation. These were some of the gains — so it was said.

Yet this was not always so. Patents, manufacturing contracts that limited markets and arrangements that gave us old technologies and machinery prevailed. Drums of trade name chemicals were sold to us at many times the price of the generic compound available in bulk. The list could be expanded.

Naipaul gave us a view of it. In his “The Mimic Men”, set in the island of Isabella, as politicians came to power their energies went into:

“… making public what already existed. We were busy. We opened schools which before would have opened their doors to children without much fanfare; we cut ribbons across brief stretches of country road; we opened laundries, shoe shops and filling stations. We were photographed with visitors from America or German travel agencies, who said the correct things; we were photographed shaking hands with the representatives of a French motorcar firm who had come to assess the potential of a regional agency. We attached ourselves to all the activity of the island and to whatever, in a territory like ours, passed for industrialisation or investment.

“An English firm began making biscuits. Someone else made toothpaste or brought down the machinery for filling tubes with toothpaste. I am not sure what it was they did. We encouraged a local adventurer to tin local fruit. This was a failure. It hadn’t occurred to anyone concerned to find out whether local people wanted local fruit tinned; no one else did either. The same man went in later for tinning margarine and was a success. The margarine was imported, the tins were imported. Our effort was to operate a machine that turned the flattened tins into cylinders. We capped one end, filled this cylinder with the imported margarine, and capped the other end. I remember the process well. I opened the factory. Our margarine was slightly more expensive than imported tinned margarine, and had to be protected. I believe the factory employed five black ladies, whom we photographed looking grave and technical in white coats.

“Industrialisation, in territories like ours, seems to be a process of filling imported tubes and tins with various imported substances. Whenever we went beyond this we were likely to get into trouble.”

Many loathed and still do, the mirror Naipaul presented. But even if the image was not a perfect representation, its reflections of distortions were not to be lightly discarded. You may ask why as an economist I choose Lamming and Naipaul to say things that can easily be represented in statistics and charts, diagrams and argument. The answer is that they do it so well, and with satire and humour. And so simply. And so briefly.

The contradictions in the process of industrialisation in Jamaica and the Caribbean require that Mr. Seaga’s new measures be put in perspective. Lewis saw the pitfalls of an indiscriminate “industrialisation” and it is this that Naipaul captures. But Lewis was able to predict the pitfalls. Why then did we fall into all of them?

Casualty of discontinued “Industrialisation by Invitation” Strategy: Abandoned Good Year Tyre Factory in the economically deprived Parish of St Thomas © Wilberne Persaud

Casualty of discontinued “Industrialisation by Invitation” Strategy: Abandoned Good Year Tyre Factory in the economically deprived Parish of St Thomas © Wilberne Persaud

Naipaul gives us some of the answers. Politicians need to boost both their egos and support. Trouble is both these “highs” are short term. Vested interest in these territories is also powerful. Lobbying the Minister in charge can get one exemptions and incentives. The “national interest” can easily be confused, even defined as coincident with individual interest.

Herein lie some of the contradictions. The JLP has been the Party most identified, initially, with the ‘industrialisation by invitation’ strategy. They are currently still pursuing a variant of it — Jamaica National Investment Promotions (JNIP), free zone, industrial estates. Yet it is the JLP that seems to be “setting industry free” by increasing stamp duties, while the PNP comes out against the policy in defense of local industry. Could it be that reducing the level of protection of domestic manufacture is thought to be the prerequisite for access to foreign funds?

Why did these measures come now? Are we witnessing the unfolding of a new strategy? Perhaps new, but not really different. Although it has not been stated, it seems apparent that the funding agencies are in favour of these policies. Here I refer to the IMF, USAID, the World Bank and perhaps others.

It is well known that these agencies believe in free enterprise. Trouble is, they believe in free enterprise abroad but not at home! We can have the 807 programme, we can have offshore manufacture that is footloose and labour intensive. We cannot have textiles in the CBI. Nor can we have free access to their markets for the manufactured items that we can most readily produce efficiently.

This reminds me of the Cuban-American Professor who said the U.S. prefers its “materials raw but people polished”. Certainly we can export raw materials without much difficulty, certainly our doctors, accountants and skilled personnel. But not manufactures or our unskilled labour. This way of seeing things from the developed world’s perspective is crippling not only to us but in the long run, to the world. I know it is a fact that in the long run we are all dead. But must we in the short run be on that heart lung machine of aid that is irrevocably if not transparently tied?

The Prime Minister may be setting forth a new strategy. One that moves away from import substitution for the domestic market and attempts to foster manufacture for export. It is evident, however, that we are still going to be restricted to the screwdriver operations, albeit for export. But in addition we will return to the merchandising of imported manufactures “from a pin to an anchor”. This strategy must lead to heightened dependence on foreign investment, foreign investors and trade. It will leave Jamaica even more vulnerable.

What we need is a thorough and real restructuring of the industrialisation effort. The emphasis must be on those things that we can potentially do best. We have to take a POLICY decision regarding technology, regarding markets, our relationship to the rest of CARICOM and fundamentally, the style of life that is culturally ours.

It is high time that we stop billing as ‘high-tech’, the mixing by recipe of a few chemicals, or the final end-processing of alcohol, while at the same time, competent scientists exist in our countries who, with a little support can do better. Drip irrigation is not new, nor is it ‘high-tech’, nor is tissue culture. Had the Japanese for instance, taken our attitude they could not have achieved their present position. We must cease confusing the form with the substance!

If we are to be more than ‘Mimic Men’ some of Mr. Seaga’s measures will be necessary. But some will have to be discarded. For success, they will all have to be informed by that POLICY initiative which apparently still has to be fully worked out. Worked out I may add, with inputs from both local and foreign experts of competence.

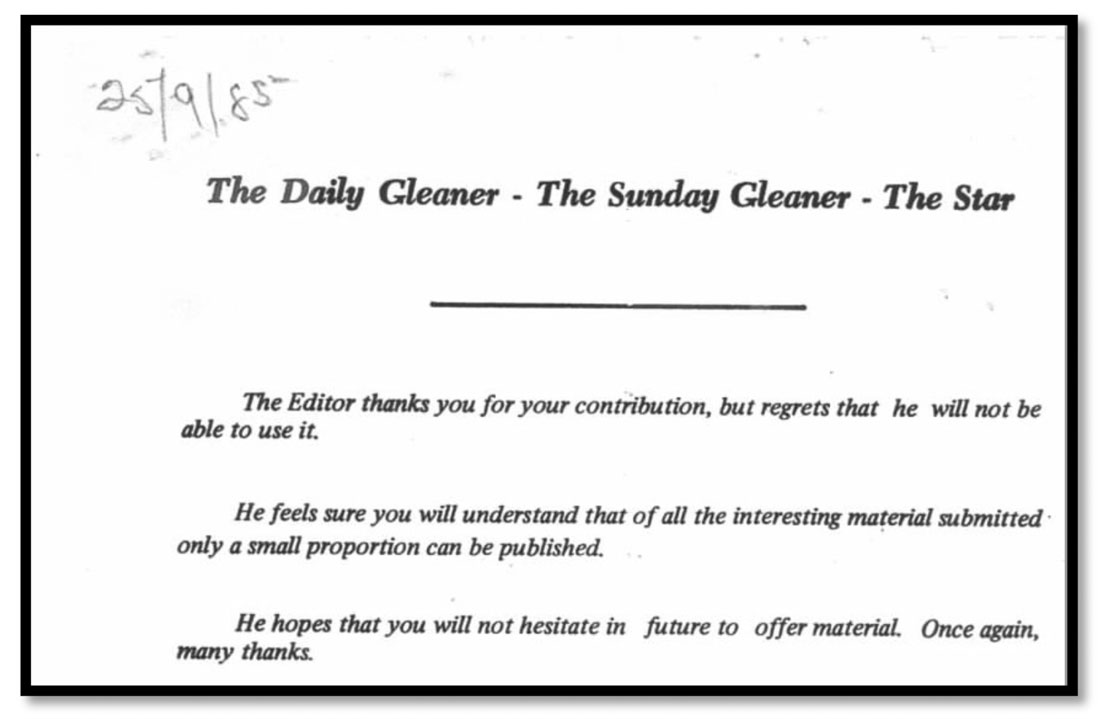

NOTE: Reproduced below is the Gleaner Editor's thanks but regret, that "... he will not be able to use" this submission — the only one of its kind in the author's long relationship with the newspaper. It's worthwhile noting this occurred during the period of 'backlash' to the ideological struggles of the 1970s that included external intervention into the politics of Jamaica 'Cold War'-style, by both the US CIA and Cuban DGI — the one against, the other for — attempted reforms of the PNP to alleviate extreme socio-economic inequality through policies associated with 'Democratic Socialist' ideas.

Regrets: Of all the interesting material submitted only a small proportion can be published.

Regrets: Of all the interesting material submitted only a small proportion can be published.