Wilberne H. Persaud, Department of Economics UWI, Mona, July 04, 2004

Great Britain’s 'Gift' – Tertiary Education for the British West Indies

“On 1 February, 1947 Thomas Taylor opened the first office of the University College of the West Indies [U.C.W.I.] at 62 Lady Musgrave Road in Kingston. The house had been the home of the leading West Indian journalist of his time, a strong opponent of those who advocated the establishment of a university in Jamaica.”[1] The College had been provided upon recommendation to the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Oliver Stanley, as a ‘gift to the people of the West Indies by the Imperial Government’. That these facts present an interesting irony is evident.

More significantly this act of generosity, delayed for centuries, represented implementation of a decision on the part of the British government that appears to have been a relatively abrupt break with the past. Indeed, prior to this development, stretching over the previous two hundred years, there had been several independent local initiatives aimed at introducing tertiary education in the British West Indies – none attracted support of Colonial Governors or the Imperial Government.[2]

As Lord Moyne noted, “efforts … to establish … institutions of university rank in the West Indies, … in spite of a frequently expressed feeling that this lack should be remedied … have come to nothing.”[3] Nevertheless, the colonial West Indian’s commitment to education was legendary. The West Indian working man or peasant woman had to perform tremendous feats of sacrifice to provide an education for the next generation. Sherlock and Nettleford illustrate this with the following:

“Any West Indian knows of peasant market women like the bone-thin elderly woman in the Duncans market in Trelawny, who, week after week, year after year, out of her meager earnings sent her son Amos Foster to Scotland as a medical student and kept him there until he qualified and returned home …”[4]

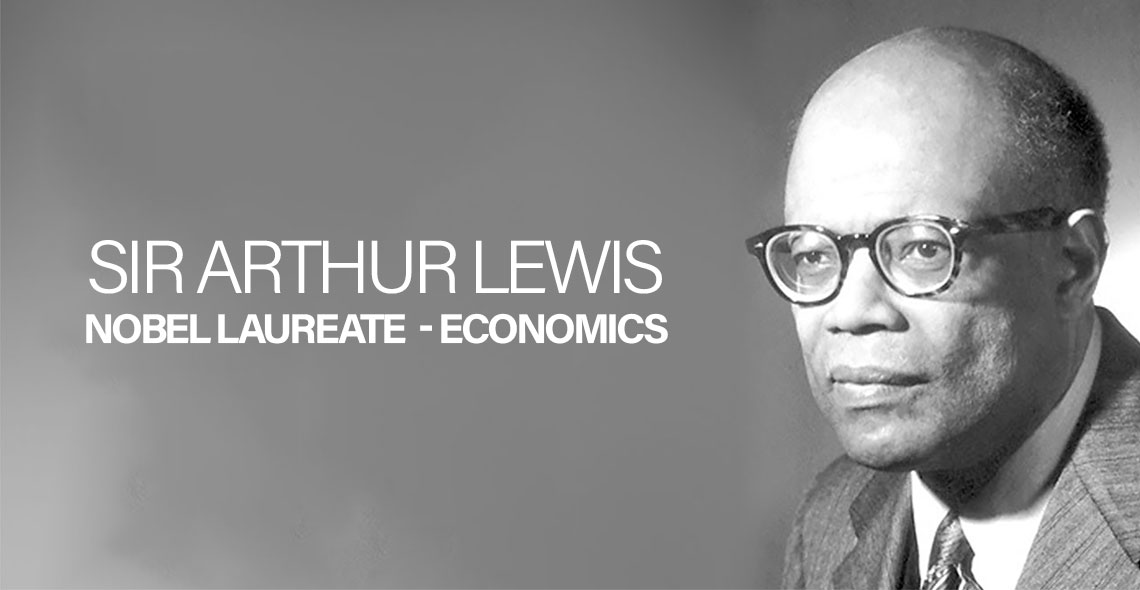

This was the surest way to climb out of the individual poverty trap. As Arthur Lewis points out in an autobiographical sketch, even the professions, really the only avenue of upward mobility for West Indians during that period, held major obstacles for locals: “I wanted to be an engineer, but neither the colonial government nor the sugar plantations would hire a black engineer, [effectively] law, medicine, preaching, and teaching were the only professions open to young blacks in my day.”[5]

Alternative pathways to social and economic mobility were either hazardous in the extreme or nonexistent. Becoming ‘Afro-Saxon’ required a level of cultural assimilation which sadly, or fortuitously happily, depending on one’s point of view, was unavailable to the majority of the population. In this context introducing tertiary education to the British West Indies in the mid 20th century therefore had immense potential for improving conditions within the society. It had the germ in it of both individual and societal material/economic as well as cultural/national upliftment.

We should not leave this brief depiction of context however, without adverting to the colonial experience of Spanish America and British North America. This late coming of Tertiary education to the British West Indian colonies is to be contrasted with the fact that: “In the half century that followed her settlement of Hispaniola (1500-1551) Spain founded the universities of Santo Domingo, Mexico and Lima …. She founded five others in the seventeenth century, and another ten in the eighteenth century.”[6

In British North America the Pilgrim Fathers founded Harvard a mere 16 years after they landed at Plymouth. These differences are stark, reflecting contrasts in approach chosen to achieve the objectives of rival European colonial enterprise, as well as that of colonies of settlement as opposed to colonies of exploitation.[7]

The Irvine Committee – Gift, Obligation, Self-interest?

In January of 1944, Secretary of State for the Colonies Oliver Stanley appointed the West Indies Committee of the Commission on Higher Education in the Colonies, under the Chairmanship of Sir James Irvine.[8] In the aftermath of World War II, preceded in the West Indies by disturbances occurring during the period 1934 to 1938 and the subsequent Moyne Commission Report, there was a relatively clear understanding that the Imperial regime could no longer operate as it did in the past. Strategic decisions were obviously taken to begin the process of weaning the colonies from the mother country.

The need for leadership and groups of professionals would become acute; places at UK universities would be insufficient to accommodate undergraduates from the colonies. A quote from Parker, who researched the development of higher education in the West Indies (Puerto Rico and the British West Indies), lays out this conclusion and even if some of his ideas may be subject to debate, or rather contest, they are worthy of consideration:

“The University College envisioned by the Irvine Committee and the Asquith Commission was initially to be more British than West Indian in character. One can argue through hindsight against a strategy chosen for creating a university in the tropics on a British model but in the climate of the times what was being offered to the West Indies was what the imperial power knew best, its own high-standard elitist concept of higher education. The British were, in a sense, giving to the West Indies and peoples of African and Asian colonies a university model of world respect. The British were taking a generous action in favouring their subject people with the best they had to offer. In another respect, however, the new colonial universities were a practical and expedient means to an end to British colonial control and responsibility. Regardless of the reasons, the people of the West Indies in 1946 were to have at last a university which eventually could be moulded and shaped to meet the developmental needs of the region. Without the concern and efforts of the Colonial Office and the planning of the Irvine Committee and the Asquith Commission, the old dream of a West Indian university could not be a new reality.”[9]

Parker hits the nail roundly on the head in at least one respect that needs to be highlighted and expanded. At the end of the war, places at UK universities could no longer be guaranteed to the British West Indian population. This, regardless of the fact that numbers would continue to be small since only a miniscule cohort of the population could afford the cost and scholarships would remain few.

More importantly, the existing places would be needed to accommodate the backlog of British students following cessation of hostilities and a return to normality in Britain. An acute need was for professionals in the medical field, accounting for the fact that the medical school at the U.C.W.I. was the first order of business.

For completeness, Parker’s notion of the British “taking a generous action in favouring their subject people” with the best Britain had to offer—the gift—should be contested. For in taking the decision to provide higher education in the colonies, including the British West Indies, the Imperial power was not abruptly and finally, having a horrific burst of bad conscience. It is this seemingly abrupt break with the past that cries out for explanation.

Carr-Saunders review of the development of facilities for higher education in the colonies up to 1945 “… revealed [no] evidence of any official interest in Great Britain in these developments until 1936 when the De La Warr Commission was appointed”.[10] In fact there were only two occasions, separated by almost a century of often turbulent colonial history,

“… on which an initiative coming from Great Britain was directed to the foundation of universities in a dependent territory under the British Crown”—the first was a “… dispatch written by Sir Charles Wood in 1854 on behalf of the directors of the East India Company and addressed to the Governor-General of India in Council”, [the second occurred when in accord with] … recommendations of the Commission on Higher Education in the Colonies which reported in 1945 — the Asquith Commission after its Chairman Lord Justice Asquith — a programme was put into operation for the development of university education in those British territories which had dependent status at that date.”[11]

Carr-Saunders provides plausible and interesting explanations at the individual, if not systemic level, for centuries of Official neglect. He also betrays the contempt, with respect to matters intellectual, in which he held British Colonial Office officials — a contempt in these matters thoroughly shared by Eric Williams. He points out that British Officials

“… displayed very little sympathy with local aspirations for university education. They had usually graduated at one of the older universities from which they carried away agreeable memories rather than professional accomplishments or enduring intellectual interests. They had little understanding of the part played in the modern world by universities and the importance of the professions for which universities are a preparation, and to them the idea of transplanting to the regions where they worked the only type of university known to them doubtless seemed fantastic. Between British officials with this background and the young and ambitious local intellectual elite there was little or nothing in common; certain virtues, probity, justice and devotion to duty, were widely exhibited by the former, but understanding of, and sympathy with, the student class were not among them. Moreover in Africa and also in Malaya British officials put their trust in the traditional social structure as exemplified in the policy of indirect rule. But the intellectual elite was in revolt against these traditional forms; in consequence the officials, regarding themselves as responsible for the simpler elements which made up most of the population of which the student class were not representative, came to think of this class as their opponents, if not actually subversive. This is what lies behind the remarks of Lord Lugard when he said in 1920 that ‘it is a cardinal principle of British colonial policy that the interest of a large native population shall not be subject to the will of a small class of educated and Europeanized natives who have nothing in common with them and whose interests are often opposed to theirs’. The same applies to Sir Hugh Clifford’s views when he said that ‘it can only be described as farcical to suppose that … continental Nigeria can be represented by a handful of gentlemen drawn from a half dozen Coast tribes — men born and bred in British administered towns situated on the seashore — who in the safety of British protection have peacefully pursued their studies under British teachers.”[12]

For us today it may be alluring to grasp the classic irony of Lugard’s and Clifford’s view of subjecting a ‘large native population’ to the will of a small group of ‘educated and Europeanized natives’ as the true manifestation of farce — akin to thousands of West Indian kindergarten children standing by the roadside, in the broiling hot sun on Empire Day singing ‘Britons, Britons never, never, shall be slaves!'

We may excuse the children, but Lugard and Clifford were far removed from the kindergarten, they were products of the ancient universities, men of the world. Thus Carr-Saunders explanation does not suffice simply because its underlying reasoning emerges from the individual and not the systemic level.

Apart from the changed circumstances at the end of World War II and the clear pressure of expediency, at least two other subsidiary, yet important impulses added urgency to the need for provision of higher education in the West Indian Colonies. First, the mass of the West Indian population took to violent protest, seemingly having had enough of quietly accepting their resultant condition of colonial exploitation. In Trinidad and Tobago (1934), St. Kitts (1935), Barbados (1937), Jamaica (1938) sugar workers erupted. In 1937 as well, Trinidad and Tobago’s oil field workers took their turn at rioting.

These ‘riots’ led to the Moyne Commission Report which highlighted to British ‘officialdom’ and beyond, the widespread wretchedness of the condition of the region’s working classes, including the appalling state of education in general — although not advocating creation of an institution of tertiary rank.[13] The negative consequences of Colonial exploitation, the impact of the great depression, the indefensible position championing democracy, fighting fascism in Europe while colonial Governors ruled single-handedly or with the help of a small oligharchic planter class in manifest conditions of deprivation — malnutrition, widespread prevalence of preventable diseases, housing conditions unfit for humans and wages inadequate for basic nutrition — all came together to present Britain with an utterly untenable situation.[14]

The second discernible impulse was a conscious decision by Britain’s ‘Official Classes’ to shore up the image of Empire and ‘Trusteeship’ — an image which had taken a beating for some time.[15]

Arthur Lewis in an exposition to the Manchester Statistical Society suggested that at a more general level, among the reasons for the new emphasis on colonial development on Britain’s agenda was the fact that there was a view held by some in Britain, the internationalists he called them, who, “seeing in colonies a source of friction and ill-will, suspect that peace might be a little more secure if colonial status could be liquidated”; in this context Lewis also discussed racism as an impediment to development in the colonies.[16]

As a matter of record however, there was indeed in Britain at the time, a general and ongoing reconsideration of colonial status—changed circumstances actually meant that the ‘Sun which never set on the British Empire’, had finally begun to appear as if in a ‘westward arc’.

Colonial populations, having been systematically denied all forms of self governance, could not then simply be abandoned to their own devices. Nor could they be left as the charges of the individual commercial companies which might be interested in their labour, plantations or raw materials—it was already clearly demonstrated that such would be a recipe for unending turbulence.[17]

Hugh Springer, himself a member of the Irvine Committee put it differently. He argued that the devastation occasioned by the great depression was “… the midwife who ministered at the birth of the West Indian nation. It also combined with other events to bring the thinking of the British government to the point where liquidation of the Empire was no longer a matter of ultimate aim but one of immediate policy. And universities came in consequence to be regarded as necessary both by aspiring nationalists and the responsible imperialist”.[18]

Was Irvine to take on the role of ‘responsible imperialist’?

The Irvine report, in a sense clinical, with little analysis or comment on the genesis and impact of the ‘history’ they cite and the resultant ‘colonial education policy’ on the people of the West Indies — a task admittedly not in their remit—points out that: “… the history, racial composition and geographical dispersion of the West Indies have been unfavourable to the development of higher education. During the greater part of their history, higher education of any kind has been almost the monopoly of the small, white, ruling minorities which, in so far as they sought it for their children, found it ‘at home’, in Britain.”[19]

In this context, it seems necessary to point out however, that whereas geographical dispersion should reasonably be expected to add to the cost—a major element of their reasoning — of providing higher education, how ‘racial composition’ as a unique element in and of itself, could be unfavourable, independent of the influence of ‘their history’ is difficult to envisage. At the time of their investigation there were two institutions of higher education in the Commonwealth Caribbean, Codrington College in Barbados and the Imperial College of Tropical Agriculture (I.C.T.A.) in Trinidad.[20]

Irvine found that: “Most of those seeking higher education seek it abroad, either at their own expense or with the help of scholarships. There is fierce competition for the very few scholarships available. An increasing number of pupils work at school for the Higher School Certificate or the University of London Intermediate Examination. Others read alone, often while holding full-time appointments, for London external degree.

In 1943, there were thus some 109 West Indians in British Universities and 250 in those of North America. About 1,200 pupils were qualified in that year through Higher School Certificate and School Certificate examinations to proceed to higher education, while in the past ten years 610 students have sat for London external degrees.”[21]

Evidently, there was a reservoir both of the young and not so young, who would benefit from higher education and as well, provide the professional cadre required in the changed circumstances the Colonial Office now confronted. But additionally, there was a common thread deeply embedded in the enterprise as Irvine saw it. There was to be an effort to create a “West Indian” graduate, seized of the historical provenance and cultural background, aware of and responsive to the extant local conditions of the region.[22]

Thus Irvine unanimously recommended “... Establishment of a single University of the West Indies at the earliest possible date. The first step should be the foundation of a University College which, in order to establish its academic standards and win public confidence and esteem should work for the most part for the external degrees of a University of repute.”[23] The college would teach basic subjects for degrees in Arts and Science, include a Faculty of Medicine and provide the centre for “a department of extra-mural studies through which its influence would be projected into all the West Indian colonies.”[24] Provision should be made for financing students both by loan funding and scholarships.

Irvine insisted on two provisions they considered non-negotiable for effective higher education in the region. Unanimously they were “... not prepared to recommend the foundation of a University ... [unless it was to be] ... a single centralized institution ... [and with] ... almost universal agreement among witnesses ... it should be entirely residential.”[25] They put the case for a single university emphatically: “So strongly do we all feel upon this point that our recommendation is for one university or no university.”

But there was a third provision, the capital cost of the institution as well as its recurrent expenditure, Irvine opined, should be a gift to the people of the West Indies by the Imperial Government — some, then as now, may have preferred it described as partial settlement of a debt obligation. That there could be any question of the local treasury finding the funds, was never at issue. So ultimately, was Parker’s view correct?

Introducing Economics

Irvine’s recommendations on the content of teaching and instruction were formulated in terms of subjects based on the commissioners’ own experience and to a much lesser degree, on the opinions of witnesses who urged particular areas of endeavour essential to filling existing gaps in what they considered to be areas of required professional expertise. Irvine suggested seven Faculties: Arts, Science, Medicine, Law, Technology, Education and Theology. Economics was to be taught in the Faculty of Arts. The embryo for later creation of a Faculty of Social Sciences was embedded here. Professors of both Economics and Political Science were to be appointed.

More significantly as a precursor to creation of a Department of Economics, the Colonial Social Science Research Council of the UK, in 1949, committed both capital and recurrent funds to create the Institute of Social and Economic Research (I.S.E.R.) at the U.C.W.I.[26] Among some of its pioneering work would of course be studies of the economies of the various colonies of the region. Economists at the I.S.E.R. included both visiting scholars and those on contract to the institution. A Department of Economics was created in the Faculty of Arts in 1955. The extant thinking of the College envisaged integration of I.S.E.R. and the new Department, with teaching for the B.Sc. Honours in Economics projected to commence in 1959.[27]

Although some of the documents on the earliest discussions of these issues have reportedly been lost to hurricane damage, there is a report that two years after creation of the Department, the Principal at a meeting of Finance and General Purposes Committee of December 18, 1957 requested advice in connection with the Chair in Economics. The Selection Board for this Chair would be two members of Council: Messrs. N.N. Nethersole and P.M. Sherlock. Reference is also made to submissions from D.J. Morgan, Head of the Department of Economics requesting funds for equipment.[28] The Department of Economics had been created in the Faculty of Arts September 1st 1955 and began teaching for a B.A. (General) with the intention of offering the B.Sc. (Econ.) thereby providing the institutional foundation stone for what would become a dynamic focal point in the quest for Caribbean Development.

Establishment

The Department of Economics in the Faculty of Arts

The Principal in 1952, at a conference of Government representatives of the Colonies served by the University, had suggested the need for extending the number of subjects the College offered. Economics was one of those specifically approved by the conference. A Senate Committee on the Institute of Social and Economic Research and the Teaching of Economics was established in academic year 1953/54.[29] Their terms of reference indicate the concerns of Senate: “To make recommendations to the Senate on (1) the integration with the College of the Institute of Social and Economic Research; (2) arrangements for the teaching of Economics in the College; (3) other relevant matters.”[30]

The actual relationship at the time, of the I.S.E.R. to the College, was something of an anomaly. If Senate harboured anxiety, as we shall see presently, their Committee dealt with that part of the issue in one fell sentence! On 29th April 1954 they made two recommendations. First, the Institute would be regarded as “having the status of a department of the College except that the source of its finance is different from that of other departments, namely, a scheme under the Colonial Development and Welfare Acts.”[31]

Secondly they concluded that a Chair of Economics not be established but instead “… a Department should be established to which lecturers should be appointed to teach Economics under the Director of the Institute. The Committee recommend that ultimately three lecturers should be appointed. It is not envisaged that teaching will begin before October 1955, but it is recommended that one lecturer, of Senior Lecturer status if possible, should be appointed as soon as possible.”[32]

Note here that the kind of certainty one might be led to infer from the assertive tone of the Senate Committee’s report is entirely unwarranted. Their recommendations, seemingly studied, considered and thoroughly adjudicated, were preliminary. Indeed there was neither a clear nor unified view within the College on the issue, particularly with respect to the academic focus of the new department — including its relationship to existing subjects taught in the Faculty of Arts for the B.A. General Degree. This actuality, but perhaps more importantly the perennial problem of funding for ‘normal’ teaching activities, coupled with uncertainty about the Colonial Development and Welfare (CD&W) research allocation to the Institute of Social and Economic Research made caution vital.

In light of this and the Inter-University Council for Higher Education in the Colonies’ Lillian Penson Committee Report, Senate on 10th June 1954 instructed the Committee to review their recommendations.[33] Penson had actually cast the proposed creation of a department of Economics in an entirely new perspective relative to the natural consequences that should flow. Noting that creation of the department was approved and financial provision made for it in the estimates ‘on a modest scale’, Penson concluded that the ‘scale’ did not appear to them to be adequate![34]

Penson also considered another suggestion alive in the College at the time—that of creating a Department of Philosophy: “It has been represented to us that this Department might serve two purposes. It might be regarded in one sense as a companion department to Economics in the Social Sciences. A subject which might be described as Government and Social Philosophy could find its place in the scheme for a B.A. General Degree just as Economics could. Secondly, it would serve the purpose of providing courses of lectures on the History of Political Thought essential for students for the Honours Degree in History and a shorter course of lectures on English Philosophy as a background to the work undertaken by students in English.”[35]

They concluded however, that this dual purpose department was not practicable as it would require too substantial an increase in staff and be too costly. But beyond this vision, the Penson Committee’s comments went even further: “…we must emphasize that once the College has started to teach ‘Economics’ it has committed itself to developing a department or a Faculty of the Social Sciences, since Economics cannot be usefully taught in isolation from other subjects, including economic history, statistics, political philosophy and political institutions.”[36] The preponderant issue was funding as well as the generally accepted notion in the College that the Institute of Social and Economic Research should provide core staff for a Department of Economics.

The CD&W research allocation had provided capital for buildings, to equip a library and provide accommodation for visiting staff of the I.S.E.R. Contract Institute staff salaries and other costs were funded by CD&W recurrent grants which also covered secretarial, computing [not to be understood in today’s terms, this referred essentially to people — tabulating numbers by hand and when necessary, with the aid of mechanical calculating machines], other technical and junior staff. The institute’s academic staff at this time — 1954 — consisted of a Director and seven full-time researchers. As it would turn out in the end, there were problems of personality and status, organizational complexity, Colonial Office policy, funding and simply logistics that had to be overcome before a full-fledged Department of Economics in a Faculty of Social Sciences could be established.

It was the understanding of the Penson Committee, from discussions with the Colonial Office, that “ … the Colonial Social Science Research Council is at present [1954] considering the future of this Institute and of similar Institutes in West, East and Central Africa … The Secretary of State for the Colonies has informed the College that ‘the incorporation of the Institute within a teaching department of the University College, under a professorial head, would be within the spirit of the original scheme and proposals to this effect would have his sympathetic consideration’. This matter is therefore now being discussed by the Senate of the College in connection with the proposals for establishing a teaching department in Economics.”[37]

Of note here is the interplay of British Colonial policy with arrangements for both research and teaching in the soon to be independent colonies of Empire. Funding was, as always and continues to be today, of immense importance. Yet the matter of focus for tertiary education and research was also hostage to the exigencies of the end of Empire. Could the University College commit to funding a Department of Economics as well as maintain its complement of researchers at the I.S.E.R.?

Choosing the latter meant that in creating a Department of Economics, given the developments envisaged as inevitable by Penson, the University College would have either to obtain substantial increases in its resources — from the not so well-off colonies that it served and was supported by — or grant funding from outside sources would have to continue, preferably at enhanced levels.

The Senate Committee on the Institute of Social and Economic Research and teaching in Economics in their second, revised report—December 6th 1954—took note of Penson arguing that in many ways the Institute and Department “… would be entirely separate, but the Committee feel that they could be of great help to each other and that there are likely to be points of interest common to both. The Committee suggest, therefore, that a joint commit-tee should be appointed, under the Chairmanship of the Principal or his deputy, to make recommendations where necessary to the Senate on matters of common concern to the Institute and the new Department. The Committee assume that the Director of the Institute and the Senior Lecturer in charge of the Department would be members of this joint committee.”[38]

Their previous recommendation with respect to timing and staffing held. A Senior Lecturer was to be appointed as soon as possible to assume Headship of the Department. As it turned out, the proposal for incorporation of the Institute within a teaching department appears never to have been officially abandoned. Halting steps were made for implementation but the merger never materialized and the Institute of Social and Economic Research, now the Sir Arthur Lewis Institute of Social and Economic Research (SALISES) continues as a separate department in the Faculty of Social Sciences still with special funding arrangements for much of its activities. The reasons for this, many and varied, we explore when we come to look at the new Faculty of Social Sciences.

In order to get Economics introduced quickly as we have seen, the department was created in the Faculty of Arts. Teaching began in October 1955. Mr. D.J. Morgan, who had been at the University of Liverpool from 1942 to 1947 as lecturer in Economics and Commerce and at the London School of Economics and Political Science (L.S.E.) thereafter, as Lecturer under Prof. J.E. Meade, joined the Faculty of Arts as Senior Lecturer in September 1955. He became Head of the Department of Economics. Indeed the 1955/56 calendar boasts a Department of one man, Morgan!

In the run-up to Morgan’s appointment, the College continued to explore ideas of the type of economics it would teach, what degree it would offer and what levels these would achieve. Dean of the Faculty of Arts, A.K. Croston had written to the Director of the L.S.E., Sir Alexander Carr-Saunders indicating the lines of the Faculty’s thinking.[39] The idea was to consolidate and strengthen the departments that were weak, i.e. number and areas of specialization of staff. In the extant quinquennial grant, there was provision for a Department of Economics to be staffed by one senior lecturer and two lecturers, as approved by the governments. I quote extensively from this exchange of correspondence for the vision it portrays of the thinking of the time.

Dean Croston indicated in his letter to Carr-Saunders that “… the idea is to teach in the first instance for the Intermediate and B.A. (General) Economics. Whether we should be able to get the money from the West Indian governments for ‘consolidation’ and for further expansion is of course problematical. Nevertheless we shall attempt to do both. So far as expansion is concerned my Faculty has thought about the competing claims of Philosophy, Geography and some subject such as ‘Government’, the last being pressed strongly by the Vice-Principal. [The Vice-Principal is Sherlock; concerned with federation and self-government hence the urgent need for ‘Government’] The Science Faculty has also considered Geography and has put it very low on its order of priority, well below Geology. My own Faculty would put it below Philosophy; and so far as philosophy is concerned, although there is much support for it, the majority of the members of the Faculty consider that it is something of a luxury in our circumstances. We feel that something of the kind of discipline offered by Philosophy could be given in a less abstract context if we aimed at some variety of the B.Sc. (Econ.) degree, with special emphasis on Government. We have decided to put this as our first priority for future development. We should regard the degree as belonging rather to Arts than to Sciences and we thought it might be possible to provide teaching for it largely by strengthening present departments. It might be most satisfactory to create a sub-department, in the History department, of Economic History. There is of course the question of direction: this might be done by a small board of studies – Dean, the head of Economics and the head of Economic History. Of course nobody here has experience of the B.Sc. (Econ.) degree and we should very much value your advice. Do you consider the kind of thing we have in mind is feasible?

To get down to details: the variety of B.Sc. (Econ) we thought suitable is the following

Part I

- Principles of Economics

- Applied Economics

- Political History

- Economic History

- Elements of Government

- History of Political Ideas

Of the alternatives, say,

- Mathematics

- An approved modern language

Part II

Government - As in the normal B.Sc. (Econ.) syllabus but perhaps with some local bias. We should, I imagine, offer Constitutional History since 1660 as the fifth paper, rather than Administrative Law or Public Finance.”[40]

Dean Croston’s and the Faculty’s idea on keeping staff costs down was to use resources already on the ground from the Mathematics department, benefit from the large overlap that would exist between the B.A. General and the new B.Sc. (Econ.) degree and as well perhaps, put in a course on Social Structure which could be taught by one of the staff of the Institute of Social and Economic Research. Whereas Croston attributes the uncertainties surrounding the B.Sc. (Econ.) degree to the College’s lack of experience in the subject, it must also at least in part, be attributed to the status of Economics as a University discipline in general as well as its yet immature status in UK Universities and the L.S.E. itself.

Carr-Saunders in response deals with three themes:

- general remarks of historical interest on development of the cultures of academic inquiry and peculiarities of British University development—clearly of interest to us even today—but important in their own right for this exercise from the viewpoint of tracing the focus the College ultimately adopted

- broad aims the College might pursue; and

- the practical problem of scarce resources and their use

On the issue of a name for the degree he points out that “The older universities award the degree B.A. to chemists, zoologists and indeed to all those qualifying for a first degree; this is absurd and is due to a strange piece of history. Likewise, London has been led to an absurdity when it calls a degree, the closest parallel to which is Modern Greats, a degree in Science. But it is not to be inferred that we think of our studies as parallel to studies in natural science.” Carr-Saunders goes on to discuss Philosophy and the other subjects Croston had mentioned, pointing out that students at large should be aware of philosophical problems.

He did as well, indicate a possible solution: “... A man with the necessary equipment and especially the necessary personality can exert a most beneficient influence in a College; the University of Malaya has been fortunate in finding a philosopher who can do just this; in other colleges a theologian may play this part and again elsewhere a ‘political philosopher’.” Preferring the latter solution he continues with the proposed inclusion of social studies in the B.A. (General) and creation of the B.Sc. (Econ.). With respect to the B.A. (General) he points out that “The London regulations mention only Economics among the subjects for this degree, but London is prepared to approve other social study subjects with Economics. For Makerere, London has approved Political Science and Sociology. ... Next as to the B.Sc. (Econ.). Since you will have three posts for economists you might as well offer Economics, Analytical and Descriptive, as well as Government in Part II. … Your economists might feel rather limited and frustrated if they were confined to teaching for the B.A. (General) and Part I of the B.Sc. (Econ.)”.

Commenting on scarce resources and the proposed new developments he goes on to examine options: “To begin with it is obvious that the provision of courses in Economics and Government for the B.A. (General) offers no difficulty. Next there is Economic History for Part I of the B.Sc. (Econ.). You would, I think, need an economic historian, i.e. someone who had specialized in that subject, and since all three posts under the head of Economics would be needed for Economics pure and applied, you would have to devote one of the four other posts for this new field. Your economic historian would not have a heavy teaching burden, and might be useful elsewhere; if he came from one of the older universities he would be primarily a historian, and able therefore to assist in the history department; if he had the B.Sc. (Econ.) qualification he could assist with Economics in Part I of the course for that degree. As to the three posts for economists, one should go to a person interested in economic theory and the history of economic thought; another should go to an applied economist. One or other of these two should be able to cover Public Finance which is an option for Part II both in Economics and Government. The third post might well go to someone who would deal with economic problems treated statistically; this subject is an option in Part II in Economics. …Assuming that with your present strength you can cover Political History, Modern Language and Mathematics, you will be all right for Part I and might be also able to offer elementary Statistical Method. Economics Part II would be fully covered. You would not cover Administrative Law in Part II of Government but that would not matter. You would also not cover Constitutional History and this is rather more troublesome.”[41]

Fluidity of the situation surrounding ideas for the Department of Economics offering the B.Sc. (Econ.) and creation of a Faculty of Social Sciences may further be gleaned from Carr-Saunders comments on ‘Government’ and departmental structure. With respect to Government, he expresses delight that it is being considered by the College, going on to point out that in his view: “…. it has an importance fully equal to that of Economics — both on its academic merits and its practical standing (incidentally it has a greater literature). Our older universities have not neglected Government; but they have not drawn the threads together; the great themes are discussed but in a disjointed fashion (at Oxford, e.g. in the schools of Greats, Modern Greats, History and so on). Our modern universities, with their more rigid departmentalism have largely neglected it (probably just because it was not recognised as a semi-autonomous field in the older universities for which the newer universities should also make provision). To my regret the recent (post-war) developments in the newer universities have been rather in the field of Sociology, Anthropology and Psychology, than of Government.”[42]

When it came to the actual departmental structure the College should institute, his presumption was that departments of Economics and Government would be set up, “… following the pattern normal in the new universities; Economic History might fall either under the History Department or the Economics Department according to the background of the holder of the post. But I might say that I have doubts about the need for a strict department structure — at least outside science and the professional schools. At the London School of Economics we manage to do without a departmental organisation in the strict sense of the word; we appoint people to teach subjects wherever the need for that subject may be. Thus we should find no difficulty in an appointment analogous to that of your economic historian it would be understood that he raught [sic] economic history wherever economic history was needed.”[43]

These discussions continued for a sustained period, in fact until teaching began in 1955. Even at the start of teaching in Economics, content of the degree appears unsettled. Firstly the problem of resources would not go away. Depending on what was to be taught, what degree to be offered, the number of ‘bodies’ and specializations would increase. Commenting to the Registrar in a letter in which he requests funding for the next triennium, D.J. Morgan indicated that when he arrived at the College, he felt “ … that the Department had reason for its existence not because it saved students going to London or elsewhere but because it offered something which London does not for West Indian Students. In the context of the B.A. (General) I conceive that to be a regional economic study of the Caribbean. I therefore drafted a course on the Economic Problems and Policies of the Caribbean which has now been approved by the Board of Studies in Economics of the University of London without amendment. In order to provide teaching for one student next session and for the present Intermediate students in the following year it is necessary to collect a substantial amount of data. I have asked for help from the Institute of Social and Economic Research in preparing this material and have contacted government officials in Jamaica and elsewhere. It seems, however, that there is no substitute for first-hand knowledge of the Caribbean and no possibility of preparing the material without a greater or lesser amount of work in Jamaica and elsewhere. …. In so far as material does exist in Jamaica it is desirable owing to the need for as much speed as possible that help should be available on a piece-basis to work over the data in preparing material for teaching and eventually for writing a textbook for the course.”[44]

Morgan’s comments foreshadow what was to become quite a controversial issue in the Department of Economics in the mid-1960s, about the need for a course which eventually came to be known as Caribbean Economic Problems. His view coincided with the vision of the Irvine Committee and those of West Indians at the U.C.W.I. and elsewhere that the unique strength of the College in its preparation of West Indians would be precisely the West Indian content of the curricula. The notion of the West Indies as the subject/object of study was central — in effect embodying ‘local’ specificity notwithstanding the need for theory, development and broadening of the mind by study and knowledge of the universal. Unfortunately, our attempts to locate Morgan’s draft of Economic Problems and Policies of the Caribbean have proven so far, unsuccessful.

Honours Economics Accelerates Plans for Establishment of a Faculty of Social Sciences

In mid 1956, discussions about the Department of Economics, its staffing, teaching and finances continued among Registrar Springer, Secretary to the Senate Committee on Estimates A.Z. Preston, and various members of the Faculty of Arts including D.J. Morgan, Head of the Department of Economics. The idea of introducing the B.Sc. (Econ.) required estimates of expenditure for the next quinquennium—a task for Morgan. The University of London’s Faculty of Economics and Political Science offered the B.Sc. (Econ.) but had different entrance requirements and a different pattern of degree from that being envisaged by the College.

Morgan proposed that there be a separation involving lecturers in Government being associated with and therefore budgeted for, in a Department of Philosophy and Government. As he put it in an August 28, 1956 letter to Preston, “I came to hear allegations of imperial expansion were being made against me. To allay such fears however unfounded, I proposed that the two lecturers in Government (one a political philosopher anyway and the other a specialist in political institutions) should be tacked on to the proposed Department of Philosophy and Government and be administered separately from my Department. I still think the division was sensible even though the initial reason for making it was unjust. However, the Estimates Committee would be seriously in error if they thought that the B.Sc. (Econ.) degree could be introduced merely by appointing two specialists in Government and offering in the third year only the Government option.”[45]

Having made his point about the nature of the proposed degree, Morgan indicated his perception of problems with respect to the content of the degree offering, the availability of funding for lecturers and provided a detailed assessment of possible solutions, including use of I.S.E.R. Staff and resources. He proposed a scheme which required appointment in Year I, of Lecturers in Economic History, Political Philosophy, Senior Lecturer in Accounting and part-time Lecturer in English Law. Statistics was to be taught in Year II. With respect to I.S.E.R he argued that:

“As far as staff is concerned, the Institute does not have a Statistician able to teach statistics. It does not have a Lawyer or an Accountant. It has no one with specialist knowledge in Industry and Trade. It has no one able to teach Economic Theory. So on the Economic side it has virtually nothing to offer that would significantly contribute to the teaching programme of the Department of Economics. The Committee may well wonder what on the economic side the Institute possesses. Apart from the Director, there are now three Research Fellows in Economics. Mr. Cumper has successively applied for the Headship, the second vacancy and the third vacancy in this Department. After his recent interview by the Inter-University Council it was reported inter alia, that: ‘Cumper has published but the work is moderate only.’ ‘Cumper, as far as we know, has no University teaching experience and showed no very positive sign of having thought, for example, how he would set about teaching Economic Principles.’ Mr. Edwards was recently considered by the Appointments Committee here for appointment to a Research Fellowship for three years. The Committee recommended his appointment by two votes to one, myself dissenting. As the grounds of my dissent are not mentioned in the minutes of the meeting perhaps I should briefly mention them here. I read the only published article available by Edwards and found that it was not up to a London M.Sc [sic] (Econ.) standard. I asked the Committee to request that the unpublished work of Edwards be submitted to his London Ph.D. supervisor for report. This was resisted by Dr. Huggins and Mr. Sherlock voted with him. I still feel that until his further work is adjudicated upon by his London supervisor I must wait and see before accepting his competence as beyond question. The third Fellow just appointed is Miss O’Loughlin. She applied for my third vacancy but was not appointed owing to doubt about her theoretical grasp.

“There are four other Fellows, two in Sociology and two in Anthropology. As I mentioned to the Committee orally, I would welcome lectures from Dr. M.G. Smith and others in the Sociology of Politics in the Caribbean. That apart I cannot think of any further collaboration possible unless and until other options were offered in the B.Sc [sic] (Econ.)

“The Committee will no doubt be aware that, quite apart from the existence of suitable specialists of the right calibre at the Institute, the Fellows would have to be available. It is the practice of the Institute to send Fellows to other areas in the British Caribbean for long periods and even those in Jamaica may for long periods be away from college when collecting data.

“To turn to resources. The Institute Library certainly will be a useful resource for students. That apart, what resources are there? We might seek permission to use some of their statistical machines [manual calculators one presumes] but we would still need one in the Department so that we had first claim on that. Otherwise there seems to be only the buildings and the finances of the Institute. With the new Arts building we shall have sufficient accommodation. That leaves finances. Use could certainly be made of finance if no conditions were imposed. But I hardly think it worthwhile working out a scheme unless the Committee gives definite instructions.”[46]

Evidently Morgan did not think much of the I.S.E.R. as a source of assistance for the Department of Economics. His standards of judgment were either quite high as they should have been, or he had hidden issues in an agenda unknowable to us from available archival materials. Taken on the face of it nonetheless, it would appear that Morgan envisaged a high quality Department of Economics, thought it his duty and was unafraid of making his views known. The fact that he chose to use the opportunity of the Estimates Committee’s request for his views on ‘four points’ to plead his entire case, suggests however, that he either did not have the ear of the top decision makers, or that they were not persuaded by his vision—a vision which they can reasonably be assumed to have at least, previously glimpsed.

Whereas our earlier comments are at best, essentially speculative, subsequent events do lend force to the view that, for whatever reasons, Morgan did not have the support of the leaders of the College. On November 23rd 1956, Morgan wrote the Principal proposing that a Chair be provided for, in the next quinquennial estimate: “In my letter of 19th November I enquired as to the machinery for creating Chairs in this College. When I called on you to-day [sic] you explained that it was open to the Head of a Department to propose, as part of his quinquennial estimates, that allowance be made for a Chair.”[47]

Morgan therefore revised his estimates supporting his proposal on three grounds. First the B.Sc. (Econ.) degree would be offered at the beginning of the next quinquennium. This he argued was a “… high-powered degree and in circumstances where it is far from easy to attract staff of the right calibre, it is inevitable that fairly senior appointments will be made in the Department. It would be inappropriate therefore for the Head of the Department not to have the status of a Professor.” Secondly he argued that once honours teaching began the Department of Economics would be of no less importance than any other. In addition “… the Head of the Department should be a Professor if he is capable of instituting and running the B.Sc. (Econ.) degree.” Finally, he submitted that “To represent the subject properly in an environment such as that of the British West Indies, where economic development has first priority and where the economic problems of Federation have yet to be faced, the Head of the Department should have the status of a Professor if he is to carry his full weight in the solution to these problems.”[48]

Evidently, Morgan’s high academic standards in declaring that the I.S.E.R.’s Cumper, Edwards and O’Loughlin were not suitable candidates for appointment to the Department were suspended when it came to discussion of a Professorship, which he justified purely on administrative grounds, and latterly, the basis of expediency. On any reading of this correspondence, it is at best extremely difficult, perhaps impossible, not to form the impression that Morgan’s proposed Chair was being created for himself!

Principal, W.W. Grave, with characteristic British ambiguity embodying an element of certainty, responds as follows:

“My dear Morgan,

This is to acknowledge your letter of 23 November [1956] in which you put forward the case for the establishment of the Professorship of Economics as from the beginning of the new quinquennium.

The Estimates Committee of the Senate has already considered this possibility along with one or two others and has agreed, without making specific recommendations one way or the other, to put them before the Senate for its consideration.”[49]

It is not clear from the Principal’s reply whether the Estimates Committee had already considered the possibility of offering a Chair to Arthur Lewis, but Grave was giving Morgan no assurances whatsoever!

Morgan continued as Head of the Department of Economics hiring Eric Wyn Evans, Peter Kenneth Newman and Robert Barry Davison. Two years later, by the 26th January 1959, his correspondence to Acting Principal Sherlock revealed he was leaving the College later in the year. W. Arthur Lewis had by this time been appointed first, Professor of Political Economy and later Principal, but was still in New York completing his assignment at the United Nations.

As plans for introducing the Honours degree in Economics were beginning to crystallize, the Penson Committee’s observation that Economics could not be usefully taught in isolation from the other Social Sciences disciplines became more evident. Indeed the decision to offer the B.Sc. (Econ) was accelerating the process towards creation of a Faculty of Social Sciences.

Teaching of Economics up to 1959 created neither an Economics degree nor an “Economist”. Candidates for the Bachelor of Arts included Economics courses amongst the set of offerings in the Faculty of Arts. Now this was about to change. With respect to the work of the Department in terms of research and advisory roles both Newman and Davison engaged in consultative work with import substituting firms during the incipient industrial development phase in Jamaica. They worked on wages, bargaining and prices.

The Department of Economics: Lewis’ Influence and the attempted merger with I.S.E.R.

With Arthur Lewis appointed Professor of Political Economy, then Principal of U.C.W.I. to take effect in October of 1959 efforts to implement the idea of a merger of the I.S.E.R. and the Department of Economics began to take on urgency not previously evident. Lewis, Deputy Director of the United Nations Special Fund at the time—1958—had requested that he be allowed leave of absence to complete his assignment there. As it turned out, he would take up full time duty at the end of March 1960. In the meantime, a special arrangement between the U.C.W.I. and the U.N. guaranteed his availability to the College for discussions and conferences without cost but for travel and subsistence expenses.

We have seen that Morgan had his own ideas about the possibilities I.S.E.R. offered, now the Director of I.S.E.R., Registrar, Lewis and others would undertake the task of designing a Department within a Faculty of Social Sciences. There were suggestions to link a Department of Applied Economics with Sociology, in addition to having a separate Department of Economics.

It appeared that imperial designs, or at least fears of it, were still being thought of as not after all, purely fictional in character or ‘unfounded’, as Morgan would have argued. Lewis, in May 1958, commenting, on recommendations embodying some of these ideas, apparently originating with Huggins, then Director of I.S.E.R., notes the following:

“There isn’t much case for linking Applied Economics with Sociology, and there is a strong case against having a Department of Applied Economics as well as a Department of Economics.

As I see the matter, Huggins should be Professor of Applied Economics within the Department of Economics, should continue to be Director of the Institute of Economic and Social Research [sic] (much cut down), and should have temporary responsibility for the Department of Sociology and for the Department of Philosophy and Government until such time as Professors are appointed in those subjects.

It is not feasible to split Economics into different Departments, and this is not done elsewhere. It is quite usual to have several Professors of Economics, each with a different title, sharing the field between [sic] them; but one of these is always recognized as bearing the prime responsibility for the subject as a whole. In American universities his position is recognized by the formal title of ‘Chairman of the Department’. In British universities there is less formality; but there is always one chair that is senior to all the others – Robbins’ chair in London, Hick’s in Oxford, Meade’s in Cambridge, mine in Manchester – and the occupant of that chair is expected to think and speak for the subject as a whole. I assume that my chair at U.C.W.I. is in the same category. I hope that one day we will have ten Professors of Economics, but they will all be members of one Department.

Huggins does not have to have a separate Department to safeguard his rights as a teacher. These are safeguarded by his status as a professor, by the democratic traditions of university departments, and by the fact that there is more than enough work for everybody. If the various Professors of Economics cannot get along together, the remedy is not to try to break up the Economics Department, but for one of them to migrate. I would not be coming to U.C.W.I. if Huggins and I had not thought we could get along together.

In the social sciences it is normal for chairs to be instituted first in economics, and for teachers of sociology and of government to be members of the Department of Economics, or otherwise working under the supervision of the Professor of Economics, until such time as separate Departments are constituted. Thus, when I first became Professor of Political Economy in Manchester, I was formally responsible for both Government and Social Administration, the teachers of which were listed in the Calendar as members of the Department of Economics …

Finally, I do not think that the Institute of Economic and Social Research [sic] should be completely dismembered. I agree with the proposition that senior members of a university should all be engaged in research. Every person of the rank of lecturer and upwards should be a full member of the teaching staff. At the same time it is useful to have a research section, consisting of junior people, to do the kind of slogging work which can be done only on a full-time basis. Most social science faculties now have a research section of this kind. Young people are appointed for one year or at most two; they have no permanent rights; they can apply for vacancies on the teaching staff; but for the most part they go into non-university jobs after their year or two as research assistants. Such Institutes are popular with the foundations; they attract funds more easily than the teaching departments. They can also take on jobs for the Government, hiring people temporarily, with funds provided by Government (federal or territorial) to do specific investigations at the Government’s request. They also provide a home for Fulbright and other visiting research fellows. Accordingly, I hope that we can keep the name of the Institute alive, with Huggins as Director. It would need funds for three or four junior research assistants only, in the Assistant Lecturer salary range, and the usual ‘laboratory’ funds, for computing assistance, typing, special library materials, etc. This is the pattern of London and the provincial universities, and of most American universities. Oxford, Cambridge and M.I.T. do otherwise; they have large research institutes with many senior members who have no teaching duties. A case can be made out for separate research institutes, but I do not see how U.C.W.I. could afford the luxury of maintaining two separate organizations, one for teaching and one for research. On the other hand the research work of the teaching department would be handicapped if we could not hire some research assistants, and have the other ‘laboratory’ facilities. The system I am recommending here seems the best compromise ...

If these suggestions are not acceptable to the parties concerned, may I ask that the matter be held over for one more session until I arrive in October, 1959? It is difficult to argue these matters at this distance, and I should feel on safer ground if I were able to size up the local circumstances.”[50]

Lewis’ influence on the nature of the Department, the Honours degree in Economics and the design of the Faculty of Social Sciences are evident from this among several other pieces of correspondence ironing out details. On a visit in January 1959 he met with Hugh Springer, the College Registrar, Huggins, I.S.E.R. Director, Morgan, Head of Department of Economics and the Bursar. Springer, characteristically meticulous in his comments on correspondence and the like, made a note of decisions taken. They covered modification of Syllabuses, staffing and sequencing of teaching in different subjects among other matters. Springer’s note indicates the following:

“Economic History – Drastic modification required; Davidson [sic], Cumper, Hall at work producing draft to be presented tomorrow morning.

Elements of Government – a small change at the end – substitution of ‘Federal Systems with particular reference to the West Indies’.

Accounting – the deletion of the one word ‘British’ from the reference to Income Tax.”[51]

In his letter to Springer written in an effort to organize meetings for this January visit, Lewis questions why the “… Honours Degree is referred to as B.Sc. Special (Econ.) instead of B.Sc. (Econ).”[52] He also points out that the proposed curriculum be subjected to significant change. Upon review of the proposals he expresses concern that:

“… Applied Economics is all about British Steel Industry etc. In part [sic] I we shall need new syllabuses in Applied Economics, and should probably also do something about the syllabus in Economic History and in the Elements of Government … [which]… will need more material on the West Indies and the Commonwealth, and less on the British Constitution.”[53]

Lewis was, indeed from the very beginning, attempting to create an economics curriculum to include the particular concerns of the West Indies of his time. Federation was foremost on the agenda. The areas of specialization of staff in economics, timing of advertisements and requirements for modification of the estimates were agreed.

Upon return to New York Lewis wrote confirming decisions of the week-end meetings. The existing syllabus for Economic History, essentially that of the L.S.E., in keeping with his general view that there should be ‘more material on the West Indies and the Commonwealth’ was to be deleted altogether and the following substituted:

“Outlines of the economic organization of Western Europe to the eighteenth century.

The international economy and European rivalries in the eighteenth century, with special reference to the Americas and the Caribbean Islands.

The Industrialization of Western Europe, the US.A., Russia and Japan in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Changes in the organization of agriculture, transport, banking, commerce and labour. Fluctuations in economic activity.

World trade in the nineteenth century, and the international movement of people and capital. The expansion of primary producing countries. The colonial system.

Social aspects of economic development. The emergence of the “welfare state”.

Economic developments between the two world wars.

Economic development of the West Indies since 1834.”[54]

Evidently, Lewis was fashioning an economic history that could shed light on the colonial condition in general and the West Indies in particular. The emphasis on world trade reflects both his own work in the subject and that of his interest in fluctuations in world economic activity. Still operating from his UN New York Office, he also immediately set about activating contacts for attracting proven scholars to the Department and Faculty of the U.C.W.I.

He used various ‘pitches’. To Kenneth Lomak, one of his former colleagues at Manchester he spoke of being ‘surprised to hear about new appointments’ in Manchester, [my inference here being either that his colleague may have been overlooked for promotion or there was an ongoing shift in the department’s focus] Jamaica’s ‘excellent climate’ and the fact that ‘there is plenty of intellectual and artistic activity both within the University and outside it; and no lack of political excitement. You would have unlimited opportunities for making yourself useful in the islands, and for enjoying yourself.’[55] He completed this particular invitation by focusing on his former colleague’s family situation as well as his proposed status at the College:

“Your children would present you with a problem at their present ages. Schools in Jamaica are good, and if the boys were going to attend the University College in Jamaica it would be simplest to bring them out. However, if they are going to go to British universities, it would seem better to leave them in their present schools. I hope you will not take it amiss that we have no chair to offer you, as it is a very small department, which will not even be commencing Honours teaching until this October. I am emboldened to ask whether you are interested in the transfer by the fact that I have myself made the same transfer without promotion.”[56]

But the weather at the College was not always reflective of that excellent climate of which Lewis boasted! In the period after Morgan left but before Lewis would have arrived, R.B. Davison acted as Head of the Department of Economics, still ‘housed’ in the Faculty of Arts. There were some interesting—from the viewpoint of college administrative and academic politics—but minor developments involving Morgan. Morgan was apparently not considered for the Chair he had succeeded in getting approved in the estimates. He tendered his resignation.

On previous occasions when he had been away, Newman acted as Head of Department. He was senior to Davison. This time it would be Davison, for Morgan had written to Acting Principal Sherlock outlining all the reasons that it would be best if Davison and not Newman took the responsibility. Sherlock thus advised and with Springer’s support, of course concurred; in fact Newman was likely to be away for some of the period. Nevertheless Newman protested that Morgan’s departure from normal procedure was based on flimsy excuses.

We are of course, scrupulously aware that regardless of protestations to the contrary, facts find it difficult to, or rather never really speak for themselves. Thus from a close reading of the correspondence it is clear that Morgan’s departing wish was to ‘demote’ Newman. He ‘arranged’ for Acting Principal Sherlock, to concur with his view before letting Newman know that indeed, it was Sherlock’s wish! In actuality Sherlock was persuaded by Morgan’s comments set before him in the previous correspondence. Upon Newman’s protestations to the Acting Principal, Springer told Sherlock he should not change his decision—‘should not’, from Springer really meant at minimum ought not, at maximum could not! [Newman was a ‘rising star’ it would seem from Lewis’ opinion of him.

Whereas he was willing to lose, or rather, offer Davison as a prospect for a position with the University of Khartoum, he wanted to keep Newman at U.C.W.I.][57]. Morgan appears as well, to express acrimony in his correspondence with Registrar Springer. He had received from Senior Assistant Registrar Hector Wynter, a copy of draft regulations for the B.Sc. (Econ.) degree meant to be sent to London for approval. For appreciation of its nuances, I quote from the letter in some detail. He begins by noting that the draft was sent to him for information, yet he was also asked for comments. [This in itself is a nudge at Wynter who ought to know better: sending material as information meant just and only that!] Morgan follows up on March 6, 1959 by spelling out his role in the process:

“As you know, I had the greatest difficulty getting the B.Sc. (Econ.) Estimates through. I proposed to offer Industry and Trade [part of what Lewis describes as ‘all about British Steel’] as the main Economics Option and Government as the main non-economics option in Part II. In addition, as far as staffing permitted, I said we might offer Economics, Analytical and Descriptive, International Economics and Modern Economic History. The Estimates were eventually agreed to. Since then much water has flown [sic] under the bridges. I will not catalogue what has gone into the water. Let us come right up-to-date. Lewis came down because you felt that in view of my decision to leave the start of the B.Sc. (Econ.) should be postponed until 1960. He decided to proceed. Since then he has been appointed Principal. Does not that alter the position once more?

It seems to me rather pathetic that not more than seven months before teaching should begin the Senior Assistant Registrar should be circulating this paper and seeking comments from members of the teaching department and one other who has never taught or taken an undergraduate degree. [This seems a reference to Huggins—Wynter’s Memo dated 2nd March 1959 was sent to Morgan, Davison, Newman and Huggins] Also the draft is incomplete for no Part II syllabus is shown. At the same time the number of Part II options is amazing. I remember being attacked by a certain person for offering too much. In that case your list is incredible window-dressing. I just cannot take it seriously.

What I should like you to take seriously is my suggestion that you are doing neither the college nor the region any good by proceeding on this amateur and spurious basis in anticipation of getting adequate staff on time and an experienced person to run the day-to-day administration of the Department. Maybe Lewis feels he can be both Principal and effective Head of the Department. In that case all is well providing it works out. If not, I think you are making a major error in proceeding with the degree for October next. I feel I should warn you of that now.

I am sending copies of this letter to the Acting Principal and to the two members of my Department.”[58]

Morgan is obviously irritated, even though we cannot know what, in his view, has ‘flown under the bridges’ or actually ‘gone into the water’! He ignores Huggins entirely—recall Huggins was Director of the I.S.E.R., which as we saw earlier in Morgan’s view, had nothing to offer the Department of Economics: the staff was all not appointable either for lacking competence in theory, being capable of only moderate work or having a competence that could not be construed as beyond question. Morgan now seemingly refers to the Director, Huggins, as “one other who has never taught or taken an undergraduate degree”! To cap it all, Morgan’s suggestion, if it might so mildly be described, is that while Lewis is bent on attempting to be ‘superman’, he clearly foresees, or rather predicts disaster.

Nevertheless, in June of 1959 the Registrar informed Finance and General Purposes Committee by way of reading a cable from “Principal Designate Professor W. Arthur Lewis… [stating] … that he had been able to secure the services of the World famous Kenneth Boulding (an English Graduate), Professor of Economics, University of Michigan for one year starting October 1959.”[59] Lewis had negotiated with the Rockefeller Foundation to cover US$10,000 of the required emolument, with the U.C.W.I. having to raise at least US$9,000 (approximately £3,150). The F&GPC discussion indicates that it was unclear from the cable whether the sum U.C.W.I. should provide was meant to cover salary, child allowance, entertainment and pension. The Registrar reported having written to Principal Designate Lewis seeking clarification on the latter. Nevertheless the committee agreed to the proposed arrangements.

After this period of preparation—almost a year—Finance and General Purposes Committee moves a “Vote of Welcome for the Principal W.A. Lewis” at the Meeting of Friday, 29th April 1960. Arthur Lewis had taken up his position full time. There were still some unsettled issues with respect to the Faculty of Social Sciences and the Department of Economics. Indeed, it was not until two months later, June of 1960 that Senate officially recommended establishment of a Faculty of Social Sciences.

The subjects to be included in the new faculty were Economics, Government, Economic History, Sociology and Economic Statistics. In addition to the Professors in the subjects specified, the Dean of The Faculty of Arts, Professors of History, Modern Languages and Mathematics would also be members of the Faculty. With respect to the Economics Department, Lewis would be titular Head while day to day affairs would initially fall to Professor Huggins, the Director of I.S.E.R. who also was designated a member of the Department of Economics.

The B.Sc. (Econ.) Part I would consist of four subjects: Paper I Economics, Paper II Political Institutions, Paper III Economic History and Paper IV Elementary Statistical Method and Sources. There were thirty four candidates registered and eligible to take the examinations of June 1960. The fees were £7. 7s.—London Fee and £2. 10s.—Local Fee. [Among the candidates were Horace Orlando Lloyd Patterson, Norman Paul Girvan and Jocelin Averil Byrne – all later to serve on the UWI staff].

Lewis at Mona

Further Preparation for the B.Sc. (Econ.) in a Faculty of Social Sciences

Lewis, when he did arrive in the third session of 1959 – ’60 to take up his position full time, commenced his task with enthusiasm. But prior to this, while based in New York his activity related to introducing the B.Sc. (Econ.) and creating a full fledged Department of Economics within a Faculty of Social Sciences continued apace. Sherlock commented on the fact that he pushed himself hard and therefore expected no less from his colleagues. This much was evident from the flurry of activity that preceded approval of the U.C.W.I. degree structure by the Board of Studies in Economics of the University of London.

Several issues had to be dealt with in order for the College to offer the Honours degree in economics: entry requirements, which at the College, differed as between the Faculties of Arts and Social Sciences; when examinations would be held; content of the offerings; who would teach and administratively who would be the functioning ‘Head’ of the Department of Economics. Apart from the difficulties presented by the short time available—it was planned to begin teaching in October 1959—staffing, administrative and personality issues, the process of establishing the B.Sc. (Econ.) was made the more complex because the London School of Economics and Political Science (L.S.E.), as Robbins had indicated, was concurrently engaged in an apparently controversial process of restructuring its own internal B.Sc. (Econ.) degree.

On the issue of staffing the Bursar foresaw a problem. Lewis, reporting to Finance and General Purposes Committee on his April 1959 visit indicated that in discussion with the I.S.E.R staff, he observed that since they had permanent appointments with the College, best practice suggested they be given appointments in the reconstituted Department of Economics. The Bursar’s disquiet centred on the fact that there had been no communication either from the Federal Government or the Colonial Office with respect to their projected support for the Institute beyond March 31st 1960. In other words, future funding for these posts was neither clear nor settled. Despite these concerns however, upon fuller discussion of the issues it was agreed that decisions of Council would take effect from October 1st 1959 as follows:

“(a) the conferring of the title of Professor of Applied Economics on the present Director of the Institute;

(b) the Appointment of Dr. M.G. Smith, at present Senior Research Fellow in the Institute as Senior Lecturer in the reconstituted Department of Economics;

(c) the appointment of the following research fellows in the Institute as Lecturers in the reconstituted Department of Economics:

Mr. G.E. Cumper

Mr. L.E.S. Braithwaite

Mr. D.T. Edwards”[60]

There was now one final matter to be ironed out. Huggins would become Professor of Applied Economics. But there was need also for a Professor of Economics, someone who would fit more in line with what Lewis had described in his letter to Springer—someone erudite and accomplished in ‘Theory’, someone who would “think and speak for the subject as a whole”. This Chair, as outlined in Lewis’ thinking in his previously quoted letter to Registrar Springer, although equivalent in status to that of the Professor of Applied Economics would be similar to the ones occupied in the British system by Robbins, Hicks, Meade and formerly by Lewis himself at Manchester. Finally there was the issue of who would be Head of the Department. It was at this point that Lewis proposed himself as Titular Head of the department. He pointed out obvious objections that could be raised but nevertheless Finance and General Purposes Committee, after discussion agreed to accept all of Lewis’ proposals.[61]

It is patently clear that Arthur Lewis’ influence over the whole process of creation of the original B.Sc. (Econ.) Honours programme requiring transfer of the Department of Economics from the Faculty of Arts to a new Faculty of Social Sciences and that of the new Faculty itself was of crucial significance. Time after time he made proposals, identified possible objections and suggested counters. Invariably his proposals were accepted. One can well imagine [we must imagine for F&GPC Minutes generally neither spelled out fine details nor attributed all specific comments] his indicating, among his conjecture of potential objections, that ideas embodying the ‘Superman’ metaphor associated with Morgan could be grounds for protestation. But he would counter them anyway. As we indicated earlier, just two months later (June 1959) he did manage to persuade Boulding to accept a Professorship at U.C.W.I. And in order to be able to do this he had to sell the idea to the Rockefeller Foundation—to the tune of US$10,000 for one year.